About Mhttps://sites.google.com/view/metamorphoses-alan-mitchell/metamorphoses-alan-mitchelle

- Alan Mitchell

- This blog was started during a half-year sabbatical from full-time art teaching at St. John's International School in 2013 to develop my painting within the context of a Masters programme, charting my developing work in progress and related interests. Since retiring from full-time art teaching in 2025 I plan to continue to make posts that chart a developing meditative practice in art and life. If you click the link in my profile you can view more work on my website.

Monday, August 14, 2023

objects with narratives ....

Thursday, April 13, 2023

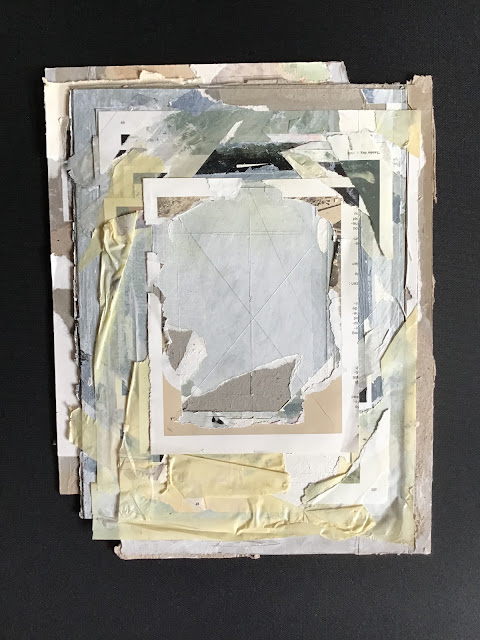

Lacuna

lacuna

- 1.an unfilled space; a gap."the journal has filled a lacuna in Middle Eastern studies"

- 2.ANATOMYa cavity or depression, especially in bone

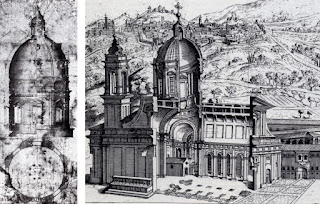

Seventeenth-century drawing of the dome (Porziuncola Museum, Vignoli 1989).

The actual patched robe of Saint Francis of Assisi which powerfully

Laudes Creaturarum

Original text in Umbrian dialect:

Notes: so=sono, si=sii (be!), mi=mio, ka=perché, u and v are both written as u, sirano=saranno

English Translation:

Wednesday, February 15, 2023

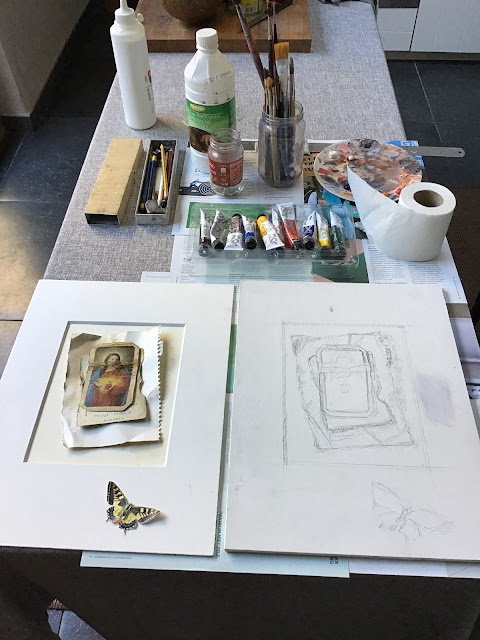

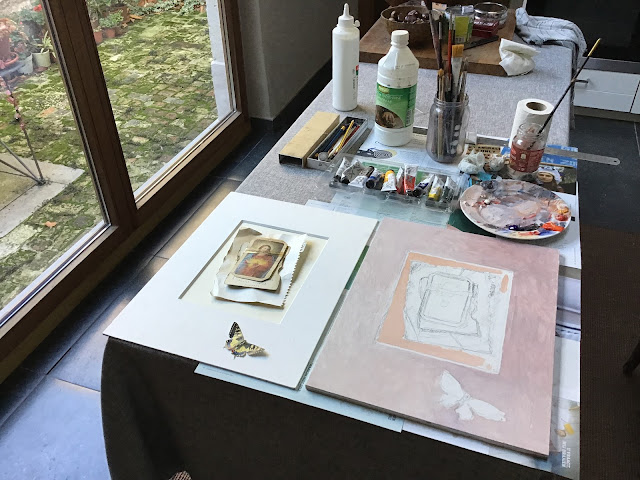

Icons of Sacred and Profane Love, Real and Illusory Images.

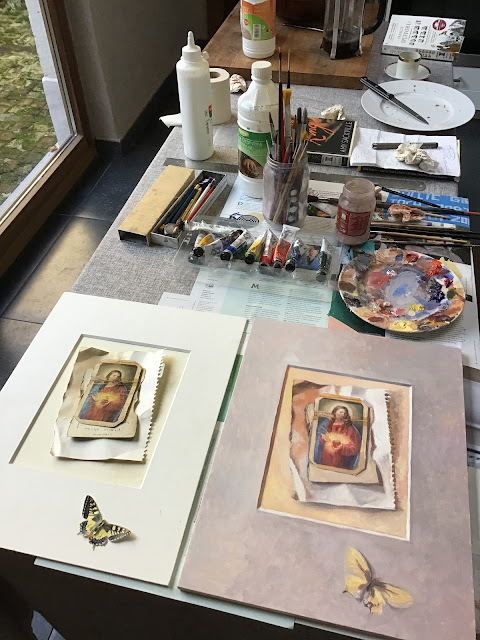

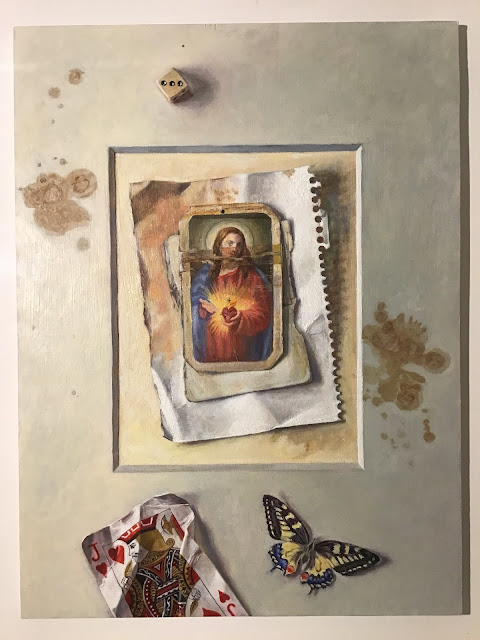

I am working on this oil painting based on a collage which includes a small ‘holy picture’ of the Sacred Heart.

This damaged, faded and fragile fragment of card, cheaply printed with an image of the Sacred Heart, now stained, cracked and creased with torn and broken edges, and yellowed sellotape repairs, belonged to my maternal Irish great grandmother ‘Ninny Grimes’, who had arrived in Liverpool as a migrant from the last Irish famine of 1879, where she managed to scrape a living by selling fruit and vegetables from a street barrow. Despite its ephemeral and transitory nature, it was an image onto which she clearly projected strong emotions, and its battered and worn condition is a testament to years of cherished handling from where she kept in in her missal or prayer book.

Holy pictures or cards, like this cheap mass

manufactured reproduction, were offered for pennies at piety stalls and other religious

places as souvenirs or exchanged between the devout with supplicatory prayers for

their particular needs for which divine intercession was sought. Along with the

saints, churches or shrines with which they were associated, they represented

the devotional art of the poor or dispossessed who placed their faith in what

these images represented, and they must have been popular with many of the

Irish Catholic refugees who swelled the ranks of Liverpool’s city slums in the

19th century and early 20th century.

The

original painting on which this cheap printed reproduction was based is a

painting by Pompeo Batoni made in 1767 which forms the central focus of an altarpiece

placed in the northern side chapel of the church of the Gesu in Rome. It became popular as the official image for the devotion to the

Sacred Heart of Jesus based on the supposed apparition of Jesus to St Margaret

Alacoque in 1673

"The Divine Heart was presented to me in a throne of flames, more resplendent than a sun, transparent as crystal, with this adorable wound. And it was surrounded with a crown of thorns, signifying the punctures made in it by our sins, and a cross above signifying that from the first instant of His Incarnation, [...] the cross was implanted into it [...]."

The fragile rectangle of paper with this printed image made a strong impression on me when my mother discovering it one afternoon, showed it to me and shared the story of her grandmother whose son, Tony Grimes, my mother’s uncle, was lost at sea during the second world war; a loss Ninny Grimes never fully recovered from. According to family legend, she would sit on the doorstep of the house and look down the street with unfulfilled longing towards the horizon from where she was always expecting him to finally appear on his way home from sea. I tried to imagine what the mother of a young son lost at sea might feel on seeing this emotional, loving, beckoning image of an ethereal, beautiful, vulnerable and suffering Christ. This tactile paper relic of my maternal great grandmother, made a tangible link for me across time to her existential angst, and her feelings of love and loss, death and the desire to be reunited.

What struck me, apart from the visceral image of a burning heart, presented to the viewer by Christ’s delicate fingers pointing to the rays of light emanating from center of his chest, was the feminized or androgynous nature of the figure itself, long before rock star David Bowie evolved his iconic alter ego ‘Ziggy Stardust’, his pre-apocalyptic fallen savior from outer space. Christ’s long hair, fair complexion and gentle wounded gaze invites us into the secret mystery he appears to be revealing, with anatomical literalness at the ‘heart’ of the image, a very corporeal spirituality derived from the Baroque original and the theology of the Incarnation.

The gaze of the androgenous Christ figure seems to invite a reciprocal personal and intimate engagement from the viewer of whatever gender. Like the mystical poetry of St John of the Cross, inspired from the biblical ‘Song of Songs’, it seems to invite the devout soul with its longing, beckoning gaze towards the burning heart of Christ himself, the metaphorical ‘beloved bridegroom’, with all the potential ambiguities this might have for an intended viewer, either a male or female. It is an image that is simultaneously both reassuring and disturbing on a number of levels.

There is a resemblance between the Pompeo painting of the Sacred Heart to the Jack or Knave of Hearts playing card in it’s familiar modern style derived from 16th or 17th century patterns, which is the third picture card who accompanies the King or Queen in each deck. A ‘Jack’ is a generic term for any young fellow, whilst a ‘Knave’ is potentially a more derogatory term for a courtier in a royal household without any particular skill who might make a nuisance of himself. Clearly this image suggests a more obviously secular or profane symbolism loaded with similar meanings and ambiguous in different context. Card games often involve chance, fate or gambolling where fickle fortune determines loss or gain. In The Tarot the Jack of Hearts can be interpreted as a person who is in love with being in love, a romantic suitor or a short-term love affair.

Objects, images or icons, despite their apparent inanimate nature, have agency. They have a way of insinuating themselves into our lives coincidently as they pass from one hand to another across time and space carrying their own coded secrets and charged with potential meanings or significance. Like a seed they can lie hidden and dormant until they are rediscovered and planted in the fertile soil of a new owner or viewer’s imagination, where they are re-animated. The liminal nature of small paper fragments, the accumulated detritus of time, constitutes a kind of archaeology of the ephemeral. The viral power of the small and insignificant to transmit mysterious or profound meanings should never be underestimated.

‘Tromp

l’oeil’ means literarly, ‘to deceive the eye’. All illusionistic painting is of the nature

of a mirror, the more real it seems to be, the more it is, in fact, an illusion.

Since vision itself is a picture according to Kepler, things perceived and

things represented, things in their true

nature and illusions are of the same basic substance.