|

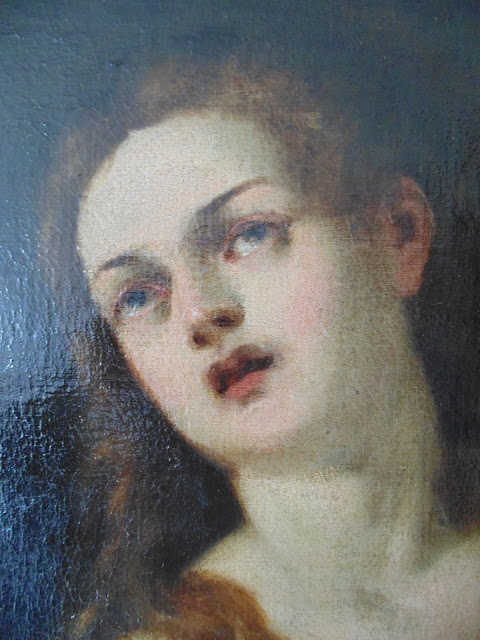

| Detail of work in progress 'Skeleton and lilies' oil on canvas. |

I had planned to spend the holidays in the UK visiting

family and in France with colleagues preparing the painting and drawing studios

for the Tasis Summer Art course in the Les Tapies in the Ardeche but as for

everyone else the global pandemic and lockdown has meant spending rather more

time than usual in isolation in Brussels, where I have a small studio and WiFi

at home in my apartment. Whilst teaching via Microsoft Teams is far from

ideal the unusually ‘becalmed’ state of the world coinciding with the Easter

Break has ironically opened a small window of opportunity to focus attention on

some current projects and give them time and space to evolve further.

|

| Skeleton and Lilies: work in progress |

I was developing an earlier investigation of the same subject, which explored through a series of careful observational drawings superimposed through time in different layers the changing forms and pattern of growth and decay of both skeletal bones and cut lilies in a vase as their stems, leaves and petals opened from buds and then gradually wilted and dried. Flowers and bones have beautiful organic forms and make wonderful subjects for still-life in the memento mori or vanitas tradition. This time I have tried to work more

with complementary colours to develop the compositional relationships within the

painting between space and form, warm and cool, light and dark contrasts and tones

Flowers are complex symbols of love, beauty and life but their fragility and transience is also a metaphor for our own human cycle of life and death, with perhaps the promise of rebirth. This is especially clear in the Greek myth of Persephone, who along with Demeter and Dionysus was a central figure in the Eleusinian mysteries, and whose decent to Hades in winter and return to the earth in the spring mirrored the periodic growth and decay observed in the seasonal and agricultural cycles.

|

| St. Benedictus from Paul Koudounaris' book, Heavenly Bodies: Cult Treasures and Spectacular Saints from the Catacombs. |

Flowers and bones have long been the key elements of the art of the reliquary. Here where matter has agency and the sacred seems to be encrypted in material DNA, artificial flowers and precious stones, form the highly complex and beautifully wrought settings for small fragments of bone or whole skeletons, tenuously ascribed to one or another saint or martyr. Death and desire united by devotion to something mystical and metaphysical through the strange alchemy of art and craft.

A little over a year ago I saw the exhibition 'It almost seemed a lily' by Berlinde De Bruyckere at Museum Hof van Busleyden in Mechelen. I was struck by how her work draws on the practice of these earlier women, who made these works as private acts of devotion, by combining the carefully wrought flowers set inside 'enclosed gardens' as shrines for relics. This clearly resonated with De Bruyckere own more surreal, fetishistic and psuedo-scientific framing and enclosing of fragmentary wax modeled human remains and found objects.

https://www.hofvanbusleyden.be/it-almost-seemed-a-lily-en

She had become fascinated by the extraordinary 'enclosed gardens' in the museums collection and had made her work in response to it. The text below in italics comes from the exhibition and explains the inspiration for the exhibition title.

A little over a year ago I saw the exhibition 'It almost seemed a lily' by Berlinde De Bruyckere at Museum Hof van Busleyden in Mechelen. I was struck by how her work draws on the practice of these earlier women, who made these works as private acts of devotion, by combining the carefully wrought flowers set inside 'enclosed gardens' as shrines for relics. This clearly resonated with De Bruyckere own more surreal, fetishistic and psuedo-scientific framing and enclosing of fragmentary wax modeled human remains and found objects.

https://www.hofvanbusleyden.be/it-almost-seemed-a-lily-en

She had become fascinated by the extraordinary 'enclosed gardens' in the museums collection and had made her work in response to it. The text below in italics comes from the exhibition and explains the inspiration for the exhibition title.

'It almost seemed a lily:' the words used in his Metamorphoses by the Roman poet Ovid – whose 2000th anniversary we commemorate this year – to describe the purple-coloured flower into which Hyacinthus is transformed on his tragic death,struck in the head by a discus thrown by Apollo. The god was in love with the handsome youth, yet snuffed out Hyacinthus’ life. Berlinde De Bruyckere views Metamorphoses as one of her ‘Bibles’. The transformation of people into animals, stones, plants and flowers – an essential element of her work – is Ovid’s handhold too in a tumble of stories that explore the great themes of human life. Here too, old tales are replete with symbolism and continue to resonate.

|

| Publication about the enclosed gardens |

Enclosed Gardens are retables, sometimes with painted side panels, the central section filled not only with narrative sculpture, but also with all sorts of trinkets and hand-worked textiles. Adornments include relics, wax medallions, gemstones set in silver, pilgrimage souvenirs, parchment banderoles, flowers made from textiles with silk thread, semi precious stones, pearls and quilling. ( this text comes from the Hof van Busleyden)

|

| Mechelen, Besloten Hofje with Saint Elizabeth of Hungary, Saint Ursula, and Saint Catherine of Alexandria, 1513–24 (?) |

Inspiration, divine or otherwise, and the hard graft of daily practice with its highs and lows is the stock in trade of both the aesthetic and ascetic life and the locus of this practice is the enclosure, the place of solitary retreat and refuge. The monk's cell or the artist's atelier are open to both the inner light of the creative imagination or divine inspiration, an interior vision that is known only within the self, and the outer light that comes from the natural course of the sun entering through a window, delineating the forms and spaces of the familiar interior world with its surfaces and material qualities and giving glimpses of a garden, cloister or a distant view of a landscape.

Contemplating flowers and bones has long been a meditation and artistic practice. Composing the elements of a still-life, building the image slowly by observing changing forms through time in space, finding the balance between light and shadow and the precise emotional register of colours and their relationships is perhaps one way of confronting a mystery that is hidden in full view.

Contemplating flowers and bones has long been a meditation and artistic practice. Composing the elements of a still-life, building the image slowly by observing changing forms through time in space, finding the balance between light and shadow and the precise emotional register of colours and their relationships is perhaps one way of confronting a mystery that is hidden in full view.

|

| Annuciation by Fra Angelico, painted onto the wall of a monks cell at San Marco in Florence |

|

| Cezanne's studio. Aix-en-Provence |

|

| Joos van Cleve, Saint Jerome in His Study, 1521, Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum. |

|

| Cow's skull with calico roses. 1931. Georgia O'Keeffe. Art Institute of Chicago |